When it comes to transportation, the future is electric. By 2025, 7 million electric vehicles are projected to be on the road in the US, with 5 million charge ports to support these vehicles. What will happen to our grid as the motor vehicle industry becomes electrified?

A number of think pieces have been published in the last few years asserting that mass adoption of electrical vehicles (EVs) might kill the electric grid. These authors have a point; the electric grid wasn’t designed to handle a couple hundred million EVs charging every day. But the way in which the grid will be “killed” may not be what these authors had in mind.

Rather than causing widespread blackouts or increasing the cost of electricity, the actual change may be more of an evolution than an extinction. EVs could usher in several significant changes to the grid that make it more distributed, more flexible, and smarter.

Sales of electric vehicles are growing fast. The Edison Electric Institute reports that up to seven million EVs could be on Americans roads by 2025, up from a little over half a million in 2016, with continued sales of 1.2 million per year. That represents around 3% of the 258 million cars and light trucks expected to be registered in the U.S. in 2025.

According to EEI, approximately 4.4 to 5.5 million charging ports, including Level 1 and Level 2 chargers in homes and workplaces and Level 3 fast chargers in public charging stations, will be needed by 2025.

The increased demand EVs will place on the grid will be enormous. A single electric vehicle can draw as much power as three new houses. Rapid chargers, in particular, draw very large loads. Utilities theoretically have the excess generation capacity to power around 75% of America’s vehicles if they were EVs. But if those EVs charge around the same time, especially during times of overall peak demand, utilities won’t be able to meet the demand.

Utilities need to match the supply of generated power with their customers’ demand for power. Demand isn’t constant, however; it varies depending on what customers are doing. For example, during hot summer afternoons demand is much higher than most other times because of the need for more air conditioning.

To meet high demand utilities either have to activate peaking power plants or buy energy from other utilities. Both options are more expensive than operating base load power plants during times of lower demand.

Demand charges and time-of-use charges are used to pass those costs on to consumers. The concern with EVs – particularly EVs charged with direct current fast chargers (DCFCs) – is that they will create higher peak demands than the grid can provide.

Several utilities, including Pacific Gas & Electric, San Diego Gas & Electric, Southern California Edison, and Hawaiian Electric, are already experimenting with time-of-use charges to send price signals that push drivers to charge during off-peak times. Some other utilities are lobbying their state utility boards to allow them to charge residential customers demand charges to provide similar price signals.

Customers pay for electricity in one of two ways: consumption, measured in kilowatt-hours (kWh); and demand, measured in kilowatts (kW). Consumption, also called usage, is the amount of energy used in each billing cycle. Demand, also called load, refers to the rate at which energy is used at any given moment. Customers on demand charge tariffs pay for the highest rate of energy use they reach – the peak demand – in each billing cycle. Most residential customers only pay for consumption. Most commercial customers pay for both demand and consumption.

However, according to the Rocky Mountain Institute demand charges “are a significant barrier to the development of viable business models to operate public DCFC networks.“

Perhaps there is a better solution.

Our turnkey process makes solar a breeze.

Learn more with a FREE consultation.

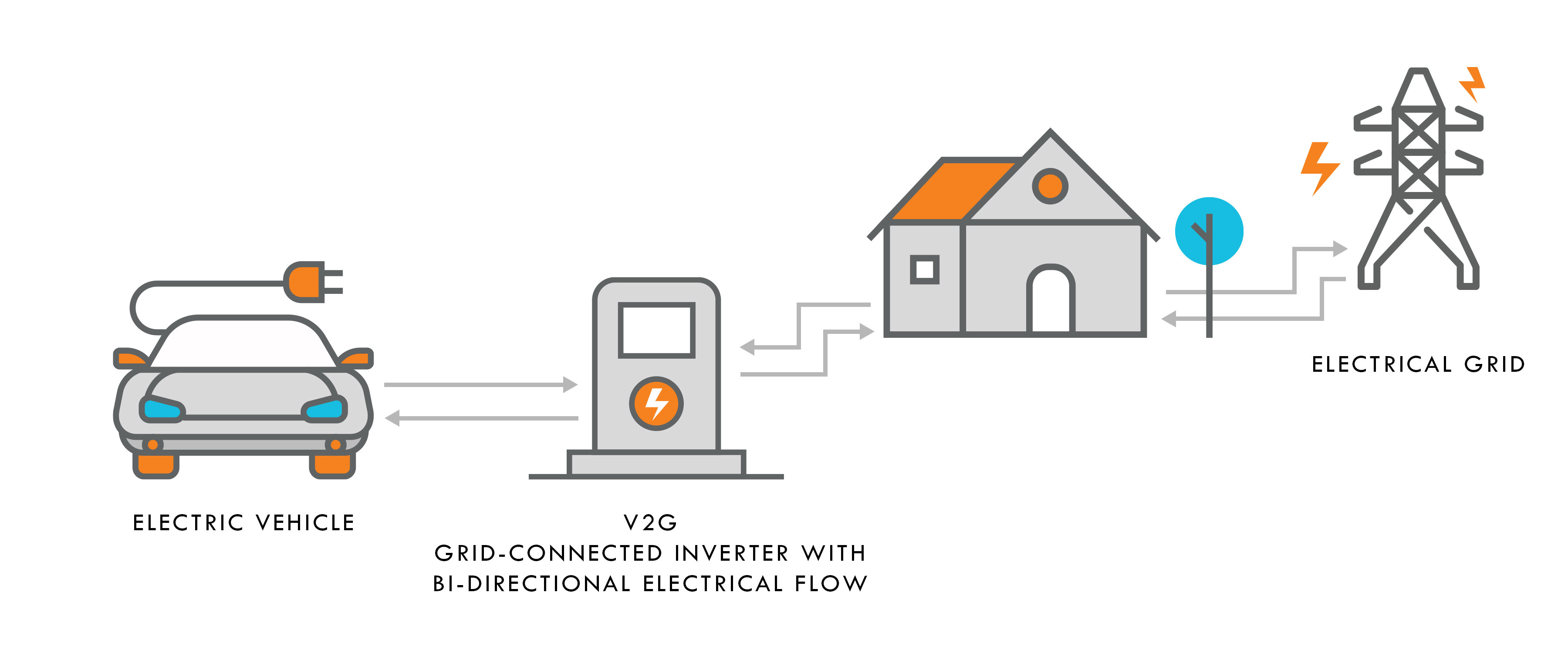

The vehicle-to-grid (V2G) concept is a system in which “gridable” electric vehicles interact with the electric grid in more sophisticated ways than just charging. V2G systems could charge intelligently at times of low cost and low demand, provide ancillary grid services like load balancing and frequency regulation, and offer vehicle owners emergency backup power or even a source of income.

These systems reduce the negative impact that large numbers of EVs could have on the grid. They offer demand response capability by reducing their own rate of charge or sending power back to the grid when needed. V2G systems also help integrate intermittent renewable energy sources like solar and wind into the grid by acting as distributed battery energy storage systems.

The National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) is actively conducting research on V2G systems. NREL researches studied plug-in electric and plug-in hybrid vehicles connected to household loads and small microgrids to evaluate their grid-connected capability. The researchers powered real home loads with Nissan Leaf and Via Van vehicles while disconnected from the grid. They evaluated the emergency power capability of these vehicles alone and also integrated real solar PV systems to extend emergency power duration. Their work shows that grid-connected EVs are viable.

V2G systems act like battery energy storage systems. Just like battery energy storage systems such as Tesla’s Powerwall and Powerpack, V2G EVs could store energy from intermittent renewable sources like solar and make that energy available whenever it’s needed.

Owning a grid-connected EV could provide all the benefits of driving an electric car and extend the usefulness of a solar array. Energy storage systems can provide peak shaving to reduce demand charges for customers on-demand charge tariffs. They can allow for greater self-consumption of solar power, which is particularly useful for customers whose utilities don’t allow 100% net metering. They can be used for emergency backup power or in microgrid applications.

Most vehicles are parked most of the time, but unlike internal combustion powered vehicles, EVs have the potential to provide useful services while parked.

Electric vehicles could act as distributed battery energy storage systems while plugged in, providing “spinning reserves” to the grid to meet sudden demands for power.

V2G systems could offer load balancing capabilities by “valley filling” – charging when demand is low and electricity is cheap, and “peak shaving” – exporting power to the grid when demand is high and electricity is more expensive.

Battery energy storage systems are already capable of providing voltage and frequency regulation – a necessity when integrating distributed generation sources with the grid. V2G systems could do the same.

Like other battery energy storage systems, V2G systems can make intermittent renewable sources like solar and wind fully dispatchable, meaning they can be used at any time. Battery energy storage has the potential to make intermittent renewables a base load power source, possibly replacing much of the coal and nuclear base load currently deployed.

EV owners may benefit even more.

EVs can store more energy in their batteries than a typical home uses in a day. With smart charge controller technology, an EV could be used for emergency backup power when plugged in at home. NREL researchers demonstrated this capability with a Nissan Leaf in their testing facility.

EV batteries may actually last longer when grid-connected. Uddin et al found that “the smart grid is able to extend the life of the EV battery beyond the case in which there is no V2G.” In simulations and a case study these researchers found both capacity fade and power fade were reduced when an EV was grid-connected in a V2G system.i

Owners may be able to monetize the grid services their EVs offer. Li et al showed that with a smart charge scheduling system, EV owners could earn $318 to $454 per year from the ancillary grid services their vehicles provide, depending on the length of their commute. They found that with a V2G system all of the popular EVs currently on the market could completely pay for the cost of electricity needed to drive 15,000 miles annually and generate a positive net profit. That means that with the right technology in place, EV owner could pay nothing for fuel and actually get paid to leave their cars plugged in to the grid.ii

Electric cars may kill the grid as we know it, but the grid that replaces it will be smarter, cleaner, and quite possibly cheaper. Grid-connected EVs are a win-win.

iUddin, Kotub, Tim Jackson, Widanalage D. Widanage, Gael Chouchelamane, Paul A. Jennings, and James Marco. “On the possibility of extending the lifetime of lithium-ion batteries through optimal V2G facilitated by an integrated vehicle and smart-grid system.” Energy 133 (2017): 710-722.

iiLi, Z., M. Chowdhury, P. Bhavsar, and Y. He. “Optimizing the performance of vehicle-to-grid (V2G) enabled battery electric vehicles through a smart charge scheduling model.” International Journal of Automotive Technology 16, no. 5 (2015): 827-837.